Introduction

For a long time Irish history had been insular, inward looking and constantly referring to our nearest neighbour, but our history and archaeology has always fit into a European context. A good example of this relates to German war refugees from 1709 who were brought to Ireland and who have over the last 300 years assimilated into the broader society. These historical refugees have a heritage in Germany, England, Ireland and further afield in North America thus connecting each of these places in unexpected ways. The Irish dimension to this story has a ‘chapter’ based in the Ballyhouras and has been explored over the last ten years by a series of community graveyard surveys (in Kilflyn/Ballyorgan and Kilfinnane) and historical research.

The Irish Palatines were ‘poor foreigners’, refugees of war and religious intolerance in the spring/Summer of 1709. They originated in the Lower Rhinelands of Germany and spread to England, Ireland and British America. Detailed research by Vivien Hick in the 1990s on the Irish Palatines forms the basis for most of our own research. As her name suggests Hick (Heck) had Palatine forebears and her job in the National Museum of Ireland allowed her to delve deeply into the material culture and heritage of Irish Palatine people, families and communities.

Broader Context

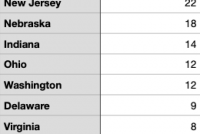

In the early 18th century, a large group of Palatines, German-speaking refugees from the Palatinate/LowerRhineland region, migrated to British America. The mass migration began in 1708/9, when the British government invited the Palatines to go to America in exchange for work. However, the influx of immigrants overwhelmed English resources and resulted in overcrowding, famine, and disease, leading to the deaths of many Palatines. The main reasons for the migration were war devastation, heavy taxation, a severe winter, and land hunger on the part of the elderly and desire for adventure on the part of the young, as well as the benevolent and active cooperation of the British government. Most of the Palatines were sent to Carolina, and New York, where they were obligated to work off their passage. Many Palatines settled in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, and their descendants can still be found in these areas today, famously called the Pennsylvania Dutch or the New York Dutch.

Many Pennsylvania Dutch families have distinctive surnames that are of German origin such as:

- Miller

- Weber

- Schmidt

- Fischer

- Bauer

- Hoffman

- Schmitt

- Haas

- Schmidt

- Fischer

Note that these are just a few examples, and there are many other common Pennsylvania Dutch surnames as well. The Bartman's of Ireland also have USA counterparts who are concentrated in particular states.

Irish Palatine Settlement

At the same time, the British government transported a group of 3,073 Palatines to Ireland. Many were settled as agricultural tenants on the estates of Anglo-Irish landlords near Rathkeale in Limerick and near New Ross in Wexford, but the settlement largely failed with many families leaving their holdings and travelling to England. Where the settlement persisted the Palatines established themselves as successful farmers and their way of life continued until the 19th century after which they became largely assimilated into Irish rural communities. These Palatine families maintained links with England and America throughout the 18th century with associated emigration. Today, there are still many names of Palatine origin present in Ireland, such as Switzer, Hick, Ruttle, Sparling, Tesky, and Fitzell. Some have converted to Catholicism but many are still Methodist or Anglican in religious practice.

Ballyhoura Palatines

After thirty years the Rathkeale Palatines expanded to the Ballyhoura region of South Limerick where the Oliver landlords took them as tenants in Glenosheen, Ballyorgan and Ballyriggin. Small farms of 30 acres were allotted at favourable rents and the Kilfinnane Palatines began an interesting three hundred years of contest, cooperation and assimilation. Nineteenth century landlords shifted their tenants about like chess pieces whether Catholic or Protestant and the economic dynamism and population growth experienced in Ireland allowed small and middling farmers to do well for themselves. Greater tensions existed between the labouring classes and the farming classes which often manifest as faction fights tied in with land agitation movements. Class war and religious wars flared up and died down over the years but the Potato blights, allied with new political ideologies developing in England, changed Ireland considerably in the mid 19th century

Surnames of the Kilfinnane/Ballyorgan Palatine families are recorded in the church records of St. Andrews (COI) in Kilfinnane and Kilflynn church in Ballyorgan. Some of the Palatine surnames such as Young (Jung) are difficult to trace to locations in Germany but others are less difficult. If the Bartmans of Ballyorgan were Palatine refugees then they have a very limited distribution in German - being found only in a small number of locations in Rhineland.

Prior to Vivien Hicks’ work the Palatines were often portrayed as innocents abroad but her work showed a more challenging history. Apparently Palatine families were each issued with a Queen Anne musket on arrival in ireland and were used as staunch Protestant militia thereafter. When the Staker Wallace was captured and tortured in Kilfinnane in 1798 Bartmans/Barkmans were explicitly referred to as amongst the militia men who flogged Wallace under Charles Silver Oliver’s orders. In the same vein Hicks and others demonstrate a link between some Wexford Palatine families’ (Hornicks are mentioned particularly) role in opposition to the Catholic labouring class Whiteboys and the subsequent massacre of Protestant families at Scullabogue, Co. Wexford, during the Battle Of New Ross in 1798. Whether the Hornicks of Wexford were proactive or reactive in response to Whiteboy agitation is difficult to ascertain but similar tensions apparently existed in Kilfinnane.

Palatine burials in the Ballyhouras are largely confined to Kilflynn and St. Andrews graveyard (COI) in KIlfinnane. It would appear some of the Palatine Jungs/Young converted to Catholicism and they are buried in Ardpatrick; while those who remained Protestant are in the two aforementioned graveyards. That these Youngs are derived from Palatine families is confirmed as they were emplyed still on Castle Oliver demesne in the 1910s as shepherds. When we try to differentiatie Catholic and Protestant headstones using iconography a key feature is the use of RIP only on Catholic headstones. As you explore Ballyhoura graveyards see can you detect any other possible clues.

This post was researched and written as part of a grassroots heritage tourism project (www.incultum.eu) in collaboration with Ballyhoura Development CLG (https://www.ballyhouradevelopment.com/), Cork Co. Council (https://www.corkcoco.ie/en) and Limerick Co. Council (https://www.limerick.ie/council). The stories were initially gathered during a community survey of the graveyard. They form part of the Historic Graves Project Destination for Ballyhoura (https://historicgraves.com/destination/ballyhoura).